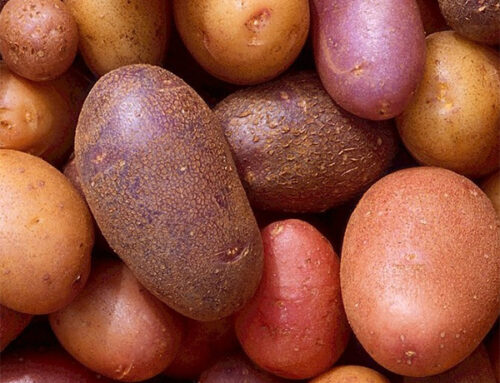

Fingerlings & Old World Potatoes

Fingerlings and Old World Potatoes are turning up in the poshest places these days. They are regular attractions on the menus of some of the country’s finest restaurants, and they even made it to the very center of power: an official White House dinner. (National Medal of Arts dinner, September 1997.)

Why all the fuss? The answer includes the novelty of their small size; their moist, waxy or dry, mealy texture; and their sometimes striking colors, including purple. Fingerlings are ideal for roasting, particularly in the juices of other foods, and give cooks sometimes subtle, sometimes dramatic variations on the potato theme. Also try par-boiling and then grilling them, or use them in salads with fennel. Or simply dice them up and fry them, and eat them as a snack food.

Going shopping for fingerlings? Better check your wallet. Their current price reflects the flashy company they keep. Though Idaho bakers are going for about $1 per pound, fingerlings are selling for two to four times that.

Of course home gardeners don’t have to pay such fancy prices. Quite the contrary, fingerlings should be even cheaper because the plants are often more productive. For instance, 1 pound of seed potatoes of a full-sized type produces 8 to 12 pounds of tubers. But 1 pound of fingerling seed pieces will produce up to 20 pounds of fingerlings.

Of course home gardeners don’t have to pay such fancy prices. Quite the contrary, fingerlings should be even cheaper because the plants are often more productive. For instance, 1 pound of seed potatoes of a full-sized type produces 8 to 12 pounds of tubers. But 1 pound of fingerling seed pieces will produce up to 20 pounds of fingerlings.

Fingerlings are (in the literal sense only) very small potatoes. Sizes vary, but most are 1 to 2 inches in diameter and 2 to 3 inches long. One, ‘Austrian Crescent’, produces tubers that are 10 inches long. Presumably, a European farmer in the sixteenth century or so pulled up one of these plants and noticed that the long, narrow, dangling tubers resemble fingers, unlike the larger, fatter kinds that resemble apples.

The most famous potato in North America is a baking type. It’s large and thick skinned, and has a dry, mealy texture that’s suited to baking or mashing. Smaller, thin-skinned potatoes, which include the fingerlings, hold their shape better after cooking. These kinds are better suited to potato salads, boiling, and steaming.

Like all potatoes, fingerlings trace their roots (no pun intended) to the Andes mountains of Peru. Though the small many-eyed, elongated fingerlings more closely resemble the wild potatoes of Peru, most are no closer to “wild” than ordinary, large baking and boiling potatoes. Two exceptions are ‘Purple Peruvian’ and ‘Ozette’. which can trace their heritage directly to Andean ancestors.

Which Fingerlings to grow:

Most varieties have red or yellow skin and yellow, waxy flesh. The two exceptions are the dry, mealy, purple-fleshed ‘Purple Peruvian’ and red-fleshed ‘Red Thumb’. The following varieties are the most popular ones in garden catalogs. Sizes are approximate; fingerling tubers may vary widely in length.

Fingerling serving ideas:

- Here’s a sampling of how some of Americas finest restaurants are serving fingerling potatoes.

- Baked with wild striped bass and shellfish broth, served with whole garlic, tomato, and olive oil. – Gotham Bar and Grill, New York

- Roasted with breast of chicken, carrots, leeks, and lemon thyme in butter sauce. – Jake’s Restaurant, Pennsylvania

- Roasted, served with seared diver sea scallops, toasted peanuts, and caramelized endive broth. – Water’s Edge, New York

- Roasted plain, served with leg of lamb and yellow wax beans and red torpedo onion. – Equus, California

- Roasted with medallions of ostrich, served with applesauce, caramelized onions, corn, tomato broth, and fall vegetables. – Sonoma Mission Inn & Spa, California

Varieties with waxy, moist flesh:

‘French Fingerling’: Silky-smooth, cranberry-red skin covers moist yellow flesh marbled with red, especially just under the skin. The 1½ by 3 inch long tubers look as good as they taste. Best steamed or roasted.

‘Rose Finn Apple’: Smooth, rose-colored skin and deep yellow flesh make this one of the most attractive and delicious fingerlings. Best eaten baked or steamed.

‘Ruby Crescent’: Ruby-skinned and yellow-fleshed tubers are 1 inch by 3 inches and often knobby (which makes cleaning more difficult). About a quarter of the tubers produced by the vigorous plants have knobby, short growths on the main tuber. These fingerlings are best roasted.

‘Russian Banana’: Yellow-skinned, yellow-fleshed, and medium-sized tubers produced in a quantity rivaling that of ‘Austrian Crescent’ make this one of the most popular fingerling potatoes. ‘Russian Banana’ tubers measure 1 inch by 3 inches. Along with perhaps ‘French Fingerling’, this variety is the one you’ll most likely find served in restaurants. Best baked, steamed, or in salads.

Varieties with mealy, dry flesh:

‘Butterfinger’: The skin is slightly rough and brown, and flesh is yellow. Full-sized tubers are about 1 inch by 2½ inches. The flesh stays firm when cooked, making this fingerling perfect for salads and steaming. This variety may also be sold as ‘Swedish Peanut’.

‘Ozette’: Yellow-skinned and yellow-fleshed tubers have deeply set eyes that spiral around the 2 by 3 inch tuber. Best roasted. This one is named for the Ozette Indian tribe of the Olympic Peninsula who adapted the variety from potatoes brought by Spanish explorers. Ozette may also be sold or listed under the alternate names ‘Haida’ or ‘Kasaan’.

‘Purple Peruvian’: Uniquely purple skin and flesh are perhaps this fingerling’s best features. The tubers measure 3/4 by 2 inches. The plant is less productive than most fingerlings. Best mashed or baked.

‘Red Thumb’: Smooth and easily cleaned red skin and red flesh make this 1 by 2 inch tuber highly appealing. The plant is very productive. This variety is best when roasted.

How to grow fingerlings:

Grow fingerling potatoes just as you would any potato. But keep in mind that all but ‘French Fingerling’ need at least 90 to 100 days of frost-free weather to produce tubers. Plant seed pieces in the garden after the last frost in your area. To avoid diseases, plant where potatoes or related plants (tomatoes, peppers, and eggplants) have not grown for at least a year.

Make fingerling seed pieces smaller than those for ordinary potatoes. Cut tubers into 1 ounce disks that have at least 2 to 3 eyes per disk. Larger potato varieties usually require a 2 ounce piece.

Set the seed pieces in 4 to 6 inch deep planting holes or trenches. Because fingerling plants are usually larger and rangier than modern varieties, give them more room than you would typical potatoes. Space seed pieces about 18 inches apart in rows 3 feet apart.

Like other potatoes, fingerlings need a loose, deep, sandy, or sandy loam soil, or soils generously amended with organic matter such as compost. Ideally, cultivate a 3 to 4 inch layer of composted manure into the planting bed early in the season. But be especially careful to keep fingerlings’ soil moist. Even brief dry periods will produce misshapen or smaller tubers.

Once the plants have emerged from the ground, hill soil up, covering all but one-third of the sprout. Repeat hilling three to four weeks later. Mulch the rows with a 4 to 6 inch thick layer of straw mulch when plants emerge to help conserve moisture and stop weed seeds from germinating.

Fingerlings are no more or less susceptible to potato pests (blights, scab, and insects such as Colorado potato beetle) than ordinary potatoes. To help prevent disease, plant certified disease-free potatoes, maintain soil pH close to 6, mulch with hay or straw, and avoid overhead watering. To control Colorado potato beetle larvae, check weekly for the clusters of orange eggs on the undersides of leaves and crush them. the larvae can be controlled by spraying Bt ‘San Diego’ when the larvae are small. Repeat spraying as the eggs hatch. The adults are not controlled by Bt ‘San Diego’, so you can either handpick the adults or spray them with pyrethrum insecticide.

Because the tubers are small, picking and cleaning can take more time than with larger varieties. The easiest cleaning method is a strong spray of water from a hose. Beware: Once you start eating fingerlings, you’ll never want to limit yourself to one type of potato again.

Courtesy of Charlie Nardozzi, senior horticulturist at National Gardening. Consultant: Greg Anthony, Ronniger’s Seed & Potato Co.